Join the colloquy

Modernism's Unfinished Business?

more

In the English-speaking world, the mention of modernism usually conjures a couple of things: famous authors (one thinks of names such as T.S. Eliot, Wyndham Lewis, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, and Virginia Woolf); and avant-garde formal experimentation, from what Eliot in his study of the metaphysical poets calls the amalgamation of disparate experience to the use of stream of consciousness as a mode of narration. In the larger, global picture, of course, modernism has been associated with innovations in photography, art, film, architecture, sound, and music—all in all with the appearance of novel techniques in the construction of imaginary, symbolic, and social time-spaces.

The issue of form remains contentious. Outside the Anglophone context, discussions of modernist engagements with form cannot fail to acknowledge the important contributions of the Russian Formalists, whose notion of defamiliarization was widely adopted in conceptual and imaginative undertakings throughout the twentieth century and beyond. The irony in this case is well-known: the Formalists were intent on de-formation as a way to renew awareness of the world, their point being that form is deadly when it becomes a mere automatized habit. The Formalists, who were given this name by their detractors, were advocates of techniques, devices, and processes that would help us disengage from fossilized form (that is, formalism); hence their emphasis on art’s potential to roughen our perception, to surprise and awaken us.

But even as modernism’s continuing influence in multiple fields and discourses owes its impetus to de-formation as both a concept and a practice, it seems imperative to raise a historical question: why did de-formation, which was, arguably, always present in the literary and artistic practices of earlier time periods, come to play such a dominant role in the avant-gardism of more recent, indeed contemporary times? What factors made the fetishizing of de-formation—a fetishizing that greatly disturbed the critic Georg Lukács—a modernist signature? With this question in mind, formal techniques such as montage (film), collage (art), stream of consciousness and polyphonicity (fiction), estrangement effect (drama), and their like begin to assume a discernible quality: these techniques’ emphases on fragmentation and disintegration, it seems, make them eminently objectifiable, reproducible, and thus fetishizable—that is to say, portable and exportable.

Part of the problem with modernism’s legacy, then, is that these portable and exportable formal markers have so traveled around the world that they have brought about another type of automatism, what Theodor Adorno, discussing the fetishistic character of modern music in capitalist society, called regression in listening. For thinkers who share Adorno’s disdain for modern mass culture, the project of modernism, even if it is an inevitable failure, has to be about recovering a reality behind the fetishes. Yet after more than a century, the modernist avant-garde legacy has become so deeply enmeshed with the commodifying forces of corporatist capitalism that the distinction between art and advertising has come to seem irrelevant. Some theorists have therefore argued that the contemporary world is a post-art world (David Joselit, After Art).

Another aspect of modernism’s unfinished business pertains to modernism’s relations with the non-elite and/or non-Euro-American worlds. Raymond Williams’s essays in The Politics of Modernism provide important examples of interrogations of the political implications of the avant-garde’s claims to revolution and social renewal. Other theorists, from James Clifford (The Predicament of Culture) to Sally Price (Primitive Art in Civilized Places), alert us to the cross-cultural dynamics embedded in modernism’s investment in primitivism. Anne Phillips’s Multiculturalism without Culture may be seen as a more recent response to what Clifford calls the predicament of culture—of culture as the unavoidable, yet precarious, arena for creative and discursive undertakings—once we accept the fact that there have been and will always be cultures (in the plural) with vast unevenness in achievements and resources.

From a certain perspective, however, the predicament of culture and the issues of multiculturalism are postmodern topics. How do we arrive at them from the origins of high modernism? What kinds of trajectories—disciplinary, philosophical, artistic, and practical—lead from the heightened interest in form, however defined (revolutionary or elitist), to the fraught, unresolved confrontations among contemporary global cultures?

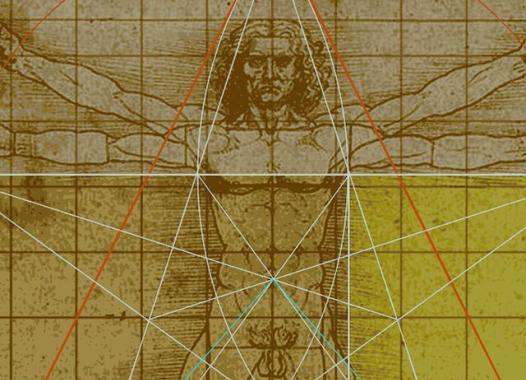

In the Western academy, one such trajectory may be traced in modernism’s immense influence on poststructuralist theory, as represented by the works of Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jacques Lacan, Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes, and Jacques Derrida. Despite their disciplinary and critical differences, what these Parisian intellectuals of the postwar period had in common was a dedication to anti-humanism. The "ends of Man" as they theorized for the European human sciences—in a mode of writing referred to as critique—have left indelible imprints on the work of subsequent generations on both sides of the Atlantic and around the globe. Can these thinkers’ dramatizations of "the age of the crisis of man"—to borrow from Mark Greif’s book title—be seen as a genealogical trait of modernism itself, and if so, how might this trait be elaborated? In the spirited announcements of the ends of Man, is there not a residual metaphysics of Man lurking somewhere?

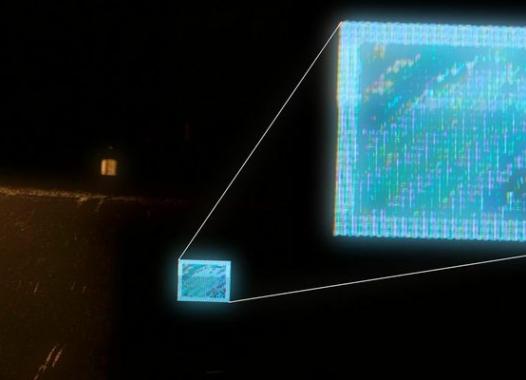

The modernist fetishization of form may also be seen as a precursor to the turn toward the posthuman, whereby the ascendancy of computational technology marks what may be regarded as the crossing of an ultimate threshold. Form in the older sense—as a crafty means of crystallizing, transmitting, storing, and redeeming human experience—is now understood by some theorists to have given way to computation as the preemptive, determinant logic, one whose interlocutors are no longer humans with imprecise sensory capacities but rather networks comprised of mathematical actants (such as algorithms). If the technological innovations of an earlier era were still centered around human creativity as such (think of the phonograph, radio, film, television, and so forth and their ties to imperfect, material human performances), those of post-electronic times rather subsume human agency to the ubiquitous regime of machinic calibrations, whose links to human experience now seem largely a matter of software programming, social control, and ever more sophisticated varieties of surveillance. The coolest modernist fetish today seems to be human experience in the form of generative data and metadata.