384

Everybody knows that some international trade is beneficial—nobody thinks that Norway should grow its own oranges. Many people are skeptical, however, about the benefits of trading for goods that a country could produce for itself. Shouldn’t Americans buy American goods whenever possible, to help create jobs in the United States?

—Paul R. Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld, International Economics: Theory and Policy

The story of the glorious labor of Hercules, when he stole the golden apples, has suggested to me the framework on which I might develop my story of the golden apples. . . . One of Hercules’ labors was to go to the gardens, kill the appalling dragon that guarded the golden apples, and bring out to the woods of Media and to the savage regions of the outskirts of civilization the apples of edible gold. So I, as he, must labor and struggle.

—Johannes Baptista Ferrarius, Frater, Hesperides, Sive de Malorum Aureorum Cultura et Usu

It is difficult, so I am told, to grow oranges in Norway. And this difficulty, while not exactly insurmountable, turns out to be one of the favorite examples for illustrating the benefits of global capitalism. As anthropologist of the fetish extraordinaire William Pietz informs, it’s this dearth of home-grown Norwegian oranges that those “secular clerics of the latter-day House of Orange,” economists Paul Krugman and Maurice Obstfeld, reach for “to bring home the point that in global free trade everybody gains, even those who are exploited in the Marxian sense that the goods they receive ‘contain’ less labor time than the goods they sell.”[1]

Climactic conditions in northern Europe (for now) preclude the cultivation of citrus fruit other than in greenhouses, the cost of which remains commercially unviable—hence the good sense it makes to import them from a warmer climate instead. “Norwegians can get more oranges for the same amount of labor by making some other commodity (refrigerators say),” observes Pietz. “Their natural resources and technology give them a comparative advantage.” It just makes better sense for “some underdeveloped nation in the tropical South (Indonesia say)” to grow the oranges. According to this feel-good logic, everybody wins. Norwegians get their oranges, and they get more of them and of a higher quality than they could hope to grow at home. Indonesians, likewise, get their refrigerators, or, actually, wait a minute, they don’t. They trade with still other nations than Norway, whose refrigerators remain entirely remote to them—something encountered only by way of the global structure of a market that tells them the price of their oranges and the cost of those refrigerators. Never mind the differential in labor time. Never mind the scale according to which both countries measure their “comparative advantages.” Things will even out eventually. Or they won’t. In the meantime, the very idea of growing oranges in Norway comes coded by a ridiculousness that almost demands that you set out for the supermarket—on principle.

Picking up the oranges that Krugman and Obstfeld deploy, Pietz diagnoses the sleight of hand by which this “Disneyfied picture of simple commodities circulating across cleanly drawn national borders” attempts to rationalize the inequalities of global exchange. Against this logic, he pits the singularizing overinvestment of the fetish, which interrupts the flow of equivalences in a market constructed as if “free” by insisting on your overweening fondness or taste for, say, this orange or that refrigerator, irrational though your attachment may seem. It is as if the local and historically particular investments of the fetish serve as a material–semiotic tariff on the abstract spaces that the self-predicating logic of global capitalism posits, creating ripples, unpredictable zones of stasis, where the “free” movement of certain commodities suddenly finds itself arrested.

In a series of now classic essays published in the mid-1980s, Pietz provided a genealogy of the fetish as “basically a middleman’s word,” a “concept-problem,” that, from its emergence as the “pidgin word Fetisso” combining Portuguese and native languages in the “cross cultural spaces of the coast of West Africa during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,” through to its recasting in Enlightenment discourses and eventually in the hands of Freud and Marx in the nineteenth century, refers to a category of things with a problematic or contested relationship to exchange.[2] Pietz demonstrates the way the “fetish not only originated in, but remains specific to, the problematic of the social value of material objects as revealed in situations formed by the encounter of radically heterogeneous value systems” (native and Portuguese; Catholic and Protestant; fetishist and psychoanalytic; capitalist and Marxist).[3] The fetish names a confusion of categories. It designates a moment in which a concern for matter and how we understand it comes to dominate the scene. Pried free from its retroactive disciplining as an irrational overinvestment or symptom, Pietz’s positive estimation of the fetish enables us to understand the way the pull of the object world upon us produces a parade of DIY sacramental objects that vie with the anchoring power of such supra or sublime objects as the Eucharist or the commodity form. Spirit, as it were, bubbles to the surface, pools, and collects in all manner of places that may prove amenable to factoring our relationship to one and other, to the world, differently—be they the co-opted dispersal strategy of a particular genus of plant twinned with the labor of its collection or going mobile (an orange) or the congealing of labor, mineral, technical resources, and energy we name “refrigerator.”

Now, the rhetorical occasion for Pietz’s debunking of global capitalism by way of Norwegian oranges was his defense of a collection of essays titled Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces (1998). At the time, Pietz worried that the book might seem “a sort of postmodern Wunderkammer, a cabinet of curiosities taken from exotic but unimportant places . . . for the amusement of intellectuals who have a taste for such things” (245). Rhetorically, he appears in the book as adjudicator cum apologist, writing an “afterward,” as he whose extra-academic, activist credentials along with the brilliance of his genealogy of the fetish stand surety for the book’s good faith. Pietz is there to see off some imagined gainsayer who coughs and sneers, “Isn’t Border Fetishisms just another of Krugman and Obstfeld’s oranges, and its readers the beneficiaries of a different order of the gains of trade?” Or, worse still, “Isn’t the book a veritable hamper of ethnographic exotics transposed from East to West, from South up North, in the ‘free’ market of intellectual exchange?” “Where’s the use-value?” “What’s to be gained?” Here is Pietz’s answer: he ventures that the collection brings to the reader’s notice a series of “heterospaces” where capitalism and noncapitalism coexist. “Rather than adapting their cultural forms to a ‘hegemonic’ or global economy or ‘resisting’ it,” “indigenous” people appropriate global commodities, transforming them back into objects in ways that defy exchange value (250). Such “border fetishisms” stand as a witness to a productive reversal of fortune “that might be termed the social appropriation of capitalism” to produce collectives that arise on the basis of and in relation to things, as opposed to the dematerializing and so empty fetishism of the commodity form. Good-bye to the bad fetish of the commodity; hello to the good, sustaining fetish relation of the retrofitted or otherwise altered objects collectively remade by the labor of these localizing polities whose forms of sociality have become thing-like.[4]

But Pietz is not content to end on this note. He remains cautious with regard to the way the collection positions these heterospaces on the edges of capital, on the periphery of its movements. Surely, such ripples, such points of arrest or pooling of rationality-defying overinvestment, must exist everywhere? Surely they inhere to the fabric of our infrastructures themselves? Accordingly, Pietz ends by saying that, in his eyes, “the notion of border fetishisms . . . can provide a useful framework for thought . . . only if one comes to terms with” something else—“the value of shoplifting” (250). For him, the “compulsion to shoplift” raises the question of “whether consumer desire is simply a utilitarian desire for more things or whether there is a deeper truth about the gratifications enjoyed in shopping?” (251). “Is some secular version of the sacred,” he asks, “in play within the compulsive pleasures of shoplifting?” Does shoplifting, in other words, rezone the sacred in a way that, if still violent, may “by some perverse logic renew the social”? “If there is an important truth here,” admits Pietz, “it is one I cannot yet articulate,” and so he ends, instead, by revealing to us the words whispered to him by the “ghost of a surgically altered old man [he] once met in Nicaragua during its brief attempt to hold back the capitalist tide” (251). This ghostly double offers that, if Pietz really wants to “understand the real ‘surplus values’ represented in the gains of trade now being reaped in the real Norway (whose national income derives primarily from its legal control over rapidly depleting North Sea oil reserves)” and “in the real Indonesia (where multinational mining firms like Freeport McMoRan and Barrick Gold are chewing up ‘resources’ to the local benefit of no one outside Indonesia’s corrupt national government),” then he “should end” his “afterward with” what he calls “an unconscionable recommendation,” a recommendation that coincidentally reprises Abbie Hoffman’s iconic, countercultural demand that we “steal this book!” (251).

It’s an odd, wonderful moment. The ghostly figure of a (is it) surgically altered and expatriate Abbie Hoffman recalls Marx’s spectral figures and dancing tables in Capital but in a way that addresses the reader, calls us out, calls for the question. Suddenly, we all have bodies again, have to take up our relation to the world of ideas and things as we register or respond to this bellowed imperative: “steal this book!” “Constitute your own heterospace,” Pietz seems to say. Inhabit the interstices of the built world in ways that try to imagine others; steal from within the flows of matter in which you find yourself. Don’t delay. For it’s done and been time to turn thief, to “survive,” “fight,” and “liberate,” to reprise Hoffman’s 1970s idiom, however those words play now in our respective times and places or translate into the emerging idiom of resilience and precarity. Who knows what is yet to happen?[5]

I ended my last chapter by taking sides, not with oranges exactly but with the structure of a feeling, a relation, a liking or taste for the fruit. Not my liking; not your liking; this liking was attributed to the long-dead warder who took the blame for a prison escape from the Tower of London in 1597. My aim was to discern the orangey remainders that punctuated texts generated by the escape and so to discern the way the vegetal time of orange-being calibrates the discourses that grew up to explain it. In the story, as recounted by the different players, the warder’s liking or taste manifests as an unstable artifact to be variously performed. For Sir John Peyton, lieutenant of the Tower, this warder’s liking becomes a rationalized set of investments or interests. He constructs him as an impecunious, gold-wanting, and so derelict, Catholic sympathizer, the likes of whom, he hopes, his recommendations for improving security will eliminate from the Tower’s labor pool. For Jesuit escapee John Gerard, the warder appears more prosaically as he who likes oranges, as he who has a “taste” (“esu delectari”) or, in Pietz’s terms, perhaps, a “fetish,” for all things “poma aurea magna,” for oranges or golden apples, for gold you can eat, fruit that jingles in the pocket.[6]

Of Gerard’s liking we know much. The oranges he gave, then shared, and then received from his warder were pressed to use as a physical therapy exercise following bouts of torture. He squeezed the oranges; saved the juice; cut and pieced the peel into rosaries. These rosaries provided him with the occasion to ask for paper with which to wrap them to send to friends and so writing paper for secret messages written in the juice. Gerard offers his Jesuit readers a lesson in the quasi-Georgic economy of an underground movement that husbands all the resources to be had in the Tower, human and not. In Gerard’s hands, then, the reproductive technology of the orange tree does not grow oranges but instead repairs his tortured body and psyche. Its cut and pieced remains pass as tokens among a circuit of friends and associates bound by their knowledge of the properties of orange juice as a medium for invisible ink. And, like Peyton, who was tasked with managing the Tower, Gerard shepherds his warder, who converts to Catholicism; wins the wayward sheep back to the fold; does so by way of an orangey (or is it golden?) incentivizing strategy, by way of “gold” the warder might literally or metaphorically eat. Whatever the warder wanted, to the extent that he knew, is lost to us. He exists now as a purely archival creature or territory allied to oranges and to gold. He exists as a liking, an orientation to oranges or to gold, and perhaps as an invitation to another way of thinking about the role of objects or other beings in configuring our polities.

In this chapter, I aim to conjure my own little theft. If both Peyton and Gerard, in different ways, steal the warder’s taste or liking from him, turning his relation to oranges or golden apples to their own ends, then I attempt to steal it back. In what follows, I seek to inhabit this liking or taste, refusing to cash the orange in or out for this or that grander narrative—be it socioeconomic, rhetorical, theological. Like the warder, I shall have to remain immanent to the rival streams of matter, orangey and golden, with which he is constructed, lose myself to the flows with which Peyton and Gerard ally him. Don’t get me wrong, I am not averse to exchange, to relationality per se, but, like the warder, I have to be content, for now, to serve as a screen that registers the way orange and oranges punctuate our infrastructures. I have to content myself with what remains and mime the gestures of a hybrid orange-man who designates one instance in which an animal and a fruit exchange properties, take their respective shares in a multispecies impression. This chapter constitutes its own order of archival heterospace, then, keyed to the ways in which orange, the dispersal strategy of particular genus of plant, by and through its recruitment of human animals, comes to interrupt acts of exchange, inclining them toward an economy of the gift or accusations of theft, and so litters our discourses with errant, erring, fragmented, time-bound polities that unfold by and through orange. Like all thefts, then, this chapter has to keep moving, actively constituting the territory it seeks to name. For, if there is, as Pietz hopes, some value to be had from a surplus, then that value has to inhere in the act itself, in my orientation to Bonner’s liking, that liking itself, already, an unruly surplus of feeling or affective attachment, in excess of a discourse of ends, already an end in itself. The issue here is not necessarily some affirmative order of biopolitics so much as it is a more neutral understanding of life and labor itself as already somehow excessive or “in excess,” and so resistant to capture. The question would be under what determinate, concrete circumstances such a surplus might enable us to create other forms of personhood and other modes of sociality or the common.[7]

Naturally, it’s a Herculean task. For oranges, or golden apples, or, indeed, sheep with unusually golden fleeces—the Greek word mala (apples) is an error or partial homonym for mela (sheep)—were, so it is said, what Hercules stole from the garden of the Hesperides.[8] Thankfully I am not alone in this endeavor. I merely follow a host of writers who, in different historical moments, have also given themselves over to the multiplicity that is orange and, after their own respective fashion, follow the pattern of Hercules’s labor or theft. Seventeenth-century Jesuit Hebraist, polymath, and art lover Johannes Baptista Ferrarius is the most explicit about this pattern. He styles his two-volume treatise on citrus culture after Hercules’s labor, though he claims to outdo the demigod (Figure 14). For whereas Hercules made off with only three golden apples, Ferrarius hands “over to your indulgence the entire Hesperidean crop, enclosed in this small volume.”[9] In place of a “club,” Ferrarius uses a pen, though as the volumes unfold, and he wanders through the orchard of trees that produce “apples of edible gold,” he comes to seem more like an overly literal suprahumanist bee, for the bee is “always very careful in [its] choice of flowers” and “especially delighted with the silvery blossoms of the golden apples.”[10]

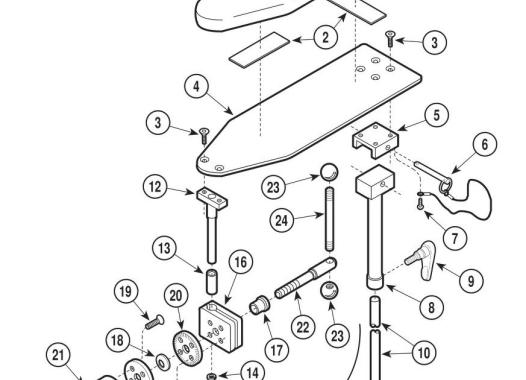

Figure 14. Hercules accepts the gift of golden apples. Johannes Baptista Ferrarius, Frater, Hesperides, Sive de Malorum Aureorum Cultura et Usu (1646). Folger Shakespeare Library Call #: SB369 F4 1646. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C.

Like all origin stories, the tale Ferrarius tells wanders. As he parses the paths taken by different writers, the story multiplies. The Garden of the Hesperides shifts location; the guarding dragon becomes an impassible sea, an all-seeing shepherd (Draco); Hercules takes the golden apples directly, tricks Atlas into stealing them for him, offloads the weight of the world upon him; the tree and the fruit change names. In the end, the fruit go mobile, are disseminated still further—or they do not; Minerva restores the apples to the garden.[11] As it moves, the story seesaws between a general economy of pure expenditure—the orange become edible gold, the precious metal become self-laboring plant that gives itself to you to eat—and a more pointed act of theft, a parasitic derivation of interest or the opening up of a restricted economy to its other.[12] The status of Hercules’s act shifts as he goes: labor, struggle, contest, trick, or thievery. The story will not settle. The promise of pure expenditure seems automatically to call forth a series of faulty, sometimes lethal exchanges. Though, as Ferrarius jokes, given their allure, the truly “Herculean task” was “limit[ing] oneself” to taking only three apples in the first place rather than making off with the whole garden, which, of course, Ferrarius’s book does, in translated form, the Hesperidean hoard become a compendium of “flowers” as he gathers all the lore and images he can.[13]

With Ferrarius, then, we encounter all manner of oranges: “golden,” “common,” “seedless,” “curly,” “starred and rose-like,” “hermaphrodite,” “distorted,” complete with their mythic explanations, as in the story of the tragic, virtuous Leonilla, “one of the best fighting Amazons of Diana,” who sought to top her success in a boar hunt by shooting a golden apple off the branch of its tree. Initially, Leonilla’s sister nymphs were rather impressed with her prowess in boar hunting, but soon they ended up in an argument over who was the best shot with a bow. A shooting match seems to provide the answer. And the nymphs are delighted with the idea. Leonilla takes the shot. The orange falls and she wins the contest (Figure 15).[14]

Figure 15. Dominicus Zamperius, Leonilla in the Garden. Johannes Baptista Ferrarius, Frater, Hesperides, Sive de Malorum Aureorum Cultura et Usu (1646). Folger Shakespeare Library Call #: SB369 F4 1646. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C

But before the fruit even reaches the ground, “blood dripped from the tree and a voice filled with tears said ‘Alas, alas, woe is me.’” Leonilla realizes that this voice belongs to her “mother, entombed in the tree,” and that she has “been accidentally pierced by the arrow.” She rushes to “embrace and help her,” but as she does so, her mother’s face appears in the bark, begs to know why this hurt was necessary.[15] And the appearance of her mother’s contorted face in the tree roots Leonilla to the spot as she herself turns tree, transforming so as to keep her mother company for all time, a living memory device that mourns by entering into a becoming orange, but too youthful, too reckless, only half-evolved; Leonilla, so we learn, comes to name the tree that sports “strange and abortive [or early] fruit” among its beautiful oranges.[16] Still, this vegetal fidelity stands surety for the bond between mother and daughter, a fidelity for which oranges or golden apples shall sometimes stand. Look closely and you can see that she is depicted in mid-transformation, her feet rooting to the ground, her face fixed on that of her mother.

In effect, Ferrarius assembles a mythic archive of the multispecies axiomatic through which orange enters our world and our imaginations. For him, “orange” eats all other modes of relation, which become secondary to this overwhelming, giddy pleasure in the alchemy of gold we can eat, of gold that goes unmined or that the world of plants mines for us. Tuned to this orange ecology that comprehends its economic tasking, that understands economy to derive from ecology, like Ferrarius, I find myself embarked on an inventory of orangey effects as hosted by this or that object or medium.[17] Choose another fruit, another color, and the story you tell and the ecology you trace will shift; connect different times and places; involve different actors. You have to begin afresh with each and every color, fruit, or thing. Though your ability to do so will be canalized by the extent to which you may be said to share the same Umwelt or environment, as, in my case, with sheep, oranges, yeast. For, more fundamentally still, this orientation to orange signals the way the phenomenology of a liking (animal sense perception) comes threaded through different ecologies. The sensory effects that we describe as “color,” “taste,” “smell,” and so on, as a “liking,” a “fondness,” even a “fetish,” might best be modeled as products of a multispecies sensory process or network that generates highly differentiated bio-semiotic-material effects for different beings, effects that then take on a metaphorical life of their own as they are translated to different registers. These matter-metaphors prove reversible. The anthropomorphic experience of color, of taste, of the senses, conjoins with a zoomorphic becoming other than oneself, a biomimetic becoming or, for the purposes of this chapter, a turning “orange” or “orangey.” Like Leonilla, women who sold oranges in Restoration theaters in England became “orange-women” or “orange-girls,” as they were called, rendering the color as hosted by the fruit mobile, stitching its presence into the visual field of Londoners.[18] Such exchanges prove commonplace. They are constitutive of what it means for us to be—all of us, like Leonilla, like these orange-women or Gerard’s orange fond warder, animate and animating everyday prosopopoeias—hybrid, walking, talking orange-sheep- people.

In what follows, I begin by imagining a world before “orange,” before the advent of the name that codifies the color, rendering it a sphere, a fruit, a thing. I then go on to tell the story of “orange’s” arrival and normalization in England, imagine its absence in one fictive future, its replacement by a different fruit and so color in another, and examine how the object world rearranges itself to accommodate its absence. Like Ferrarius, then, this chapter appears in the guise of a book of flowers, a florilegium keyed to the hyperoccasional gatherings that each orange or liking for oranges engenders. Or, perhaps it is a dance, a tracing and tracking of the steps that our animation by oranges, our taste for the fruit, produces. I am not sure that this little book of flowers or surplus of dance steps will offer much by way of consolation. The movements or gatherings I record may constitute dull routines or generate spectacular surprises. They remain partial, ephemeral, subject to dispersal. Dances end; posies wilt, change their hue, find themselves replaced by still other gatherings. Time passes. And that passage registers differently according to the vagaries of our biosemiotic motors. Oranges, for example, change their color depending on their exposure to temperature. In the tropics, they are not necessarily orange at all, but green. And as they decay, they turn white, blue, black, as the polities of bacteria they host “flower.”

Still my hopes are manifold. I hope that modeling an archival heterospace tuned to the way oranges derange rationalized modes of exchange might, in some small way, make good on Pietz’s kleptomaniacal imperative. Perhaps siding with oranges (and, on occasion, refrigerators), with certain historically particular configurations of labor, matter, and energy, might enable us to “renew the [concept of the] social” athwart the lines of species such that questions of economy might, once again, be understood to derive from a general, even extraterrestrial ecology, an ecology that refuses the hyperreference of terrestrial grounding.[19] What would a polity or sense of the common generated by or through oranges look like? We can begin to measure its presence and charting its contours by traveling our discourses by way of the disturbed exchanges and disturbance of exchange an orange causes.

Before Orange, circa 1460

“Richard of York,” we know from the early-twentieth-century rhyme cum mnemonic device, “gave battle in vain,” but at the time of the Battle of Wakefield (1460), which he lost and at which he died, the word orange had only just entered the English language and had only just come to designate the color phenomenon that occurs, in the visible spectrum, at a wavelength of about 585–620 nanometers. Without doubt, Richard of York’s supporters sang songs to remember a good many things. But when seeking to name the phenomenon we name “orange,” they reached for an altogether different constellation of words to designate the range of tones and shades of things that hosted the color in their object world. White roses sported your allegiance to the House of York, distinguishing you from the red, red rose of the House of Lancaster, but if there were such a thing as an orange rose, it had yet, in English, to become “orange.” The words pome d’horange, oronge, orenge, orynge, and oringe, designating the fruit, appear around 1400. But the extension of the word to include any color resembling the skin of an orange is not widely credited before the 1550s.[20] When met with the phenomenon, Richard of York and friends were not open-mouthed or mute. They merely reached for different color words to describe the sun, a marigold, Herod’s hair and beard. Even the oranges that Hercules stole from the Garden of the Hesperides or that Venus gave to Hippomenes in order to beat Atalanta posed no problem, for they were not (and may never have been) “orange” or, for that matter, oranges.[21] They remained pomum aurantium, golden apples, or, as rendered in Neo-Latin, in homage to the citrus collections of Italian nobility, medici.[22]

Codifying the practices of limners or portrait miniaturists in England, such as might once upon a time have painted Richard of York, in small, from the life, Edward Norgate’s Miniatura or the Art of Limning (circa 1627–28) looks back over the techniques used to craft the jeweled worlds of fifteenth-and sixteenth-century English portrait miniatures. He synthesizes the techniques of his artisan forebears, Isaac Oliver, Nicholas Hilliard, Lavinia Teerlinc, and the color palettes of his time. “The names of the Severall Colours commonly used in Limning are these,” he writes: “white,” “yellow,” “red,” “green,” “browne,” “blew,” “blacke.”[23] These colors sport a host of medial hues, each of which has its own peculiar temperament according to the nature of the ingredients from which it is mixed. Yellow subsumes “Masticot, Yellow Oker, English Oker”; red, “Vermillion, Indian Lake, Red Lead.” Each derives from a working of plant and mineral and insect ingredients, such that the limner had to do more than simply know her colors. She had to know their temperaments, their likes and dislikes; she had to know which were “friends” and “foes.” “English Oker,” writes Norgate, “is a very good Colour and of very much use. . . . It is a friendly and familiar colour and needs little Art or other ingredient more.”[24] But contrast this friendly color to the treacherous “Ceruse” (a white), which “will many times after it is wrought tarnish, starve and dye” and, weeks after it is applied, “become rusty reddish, or towards a dirty Colour.”[25] Norgate goes on to describe a lengthy process by which ceruse might be rendered semistable by enlisting the aid of another, more friendly substance—the “hungry and spungie chalk,” which will “suck out” all “the greasy and hurtfull quality of the Colour.”

Less schematic in its organization, Nicholas Hilliard’s short Treatise Concerning the Arte of Limning (circa 1600) codes this practical knowledge of the properties of different substances within an explicitly moral philosophical framework. For Hilliard, still the artisan, working hard for the gentrification of his art, the temperament of the limner proves as crucial as the temperament of the ingredients:

The best waye and meanes to practice and ataine to skill in Limning, in a word befor I exhorted such to temperance, I meane sleepe not much, wacth [sic] not much, eat not much, sit not long, usse not violent excersize in sports, nor earnest recreation / but dancing or bowling, or little of either, / then the fierst and cheefest precepts which I give is cleanlyness, and therfor fittest for gentelmen, that the practicer of Limning be presizly pure and klenly in all his doings, as in grinding his coulers in place wher ther is neither dust nor smoake, the watter wel chossen or distilled most pure.[26]

The limner must curb her behaviors; she must practice temperance in all things so as to be able to temper the colors, manage the unmanageable liveliness or deadness of certain ingredients learning which colors she can rely upon, such as the friendly yellow oker, and which require careful supervision, as in the fickle ceruse. In a historical moment when color fixity was the very emblem of scarcity value and pigments could turn fugitive and fade, the limner required a specialized knowledge of the etiquette of color, learning to pamper and flatter such substances that might provoke sympathetic color effects. In Bruno Latour’s terms, we might suggest that here the limner must seek out friendly agencies, adapting her gestures in the hope of maintaining alliances that would keep color effects still.

Hilliard would have to wait for the ministrations of Henry Peacham’s successively revised and enlarged The Compleat Gentleman (1622) for the ministrations of the limner to her ingredients to be accorded gentlemanly status.[27] But, eventually, his attentiveness or politeness to colors would lead to the inclusion of the art among pastimes deemed gentlemanly. In the enervated lexicon of the Treatise, however, such gentility manifests as an almost obsessive attention to the “fineness” and “purity” of the art. The word “pure” assumes a unique redundancy in the treatise as he seeks to name the quality of attention and behavior required of the limner in attending to the vagaries of colors whose qualities she inventories. The word “pure” comes to describe both the person of the limner and the materials she handles, purity becoming, in essence, a common property or product in the making, to be proved by the effect of the finished miniature on the viewer. The labor of the limner stands in reciprocal relation to the final stability of color in the miniature. Her husbanding of the materials, her artful handling of foes and reliance on friends, records a joint exercise in making that understands poiesis as a cascade of competing agencies.[28] You may neglect the friendly ochre, but on no account skimp on your attention to the ceruse. Keep your chalk dry until you need it.

Hilliard and Norgate’s expertise speaks to what Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari describe as the artisanal devotion to the “prodigious idea of Nonorganic Life,” the agency of all the substances called upon in the acts of making and manufacture they set in motion.[29] Their treatises read like strange Georgic manuals, husbandry books, or participant-observation ethological studies of the animal behavior of minerals, all to obtain very particular qualities of color. Belonging to the long tradition of lapidaries, which describe the particular virtues (force or agency) of gemstones and minerals, both follow Aristotle’s theory of substances, for which color was understood to be contingent on physical variables.[30] As Bruce R. Smith summarizes, the “color [red] happens only in the presence of fire or something like fire.”[31] Color manifests, then, as a form of affect or sympathy between materials that “contain . . . something which is one and the same with the substance in question.” What matters for Aristotle and for the limner most is a color’s brightness, its saturation of a medium. For Hilliard and Norgate, this saturation, effected by differing processes in every case, leads to color fixity. Such then was the essence of their skill—the art of keeping colors still by cultivating or rerouting the desires of substances.

The salutary lesson of imagining a world before “orange,” a world of saffron and ochre and yellows, lies not in a hardline historical epistemology that would cry foul and insist that there was, at that time, no such color. On the contrary, the absence of “orange” foregrounds instead the way color, like any complicated phenomenon, constitutes a “sheaf of temporalities” or a “knot in motion” that connects different times and places and different entities in a structure of only apparent simultaneity.[32] The emergence of the word orange represents a formalizing event keyed to the production of an infrastructure that yokes the color phenomenon to the fruit as it works its way from Asia to the Americas and thus sets in motion a set of routines for making persons and worlds by threading together or knotting otherwise asynchronous chronologies (ecological, social, political, sexual, religious, and so on). The word or ethonym orange constitutes a partial archive of this process. Remove the fruit, cancel the various substrates that host “orange,” or offer new ones, and the effect that is “orange” will alter. This is as true now as it was then. For even today we have trouble keeping our colors straight and are unable, in the absence of some guaranteeing medium, to call up an exact shade with certainty. Keyed to the rainbow as captured by Newtonian optics, the mnemonic “ROYGBIV” aims to keep something straight that is not, to manage the set of effects named “color” as they occur at the interface that is the human sensorium. Learn the rhyme and you will remember the order of colors in the rainbow. But, while the mnemonic assumes a post-Aristotelian orientation to color, it retains, in shifted form, the order of labor and politeness toward matter that Hilliard and Norgate advertise via their husbanding of ingredients to their limning. This focus on the unreliability or the drift to color reorients our attention toward those kinds of practices or routines that keep phenomena still, regularize them, and with what order of politeness or hospitality they do so.[33] It invites us to attend to the ways in which certain operations are conserved, dropped, or redistributed into different discourses or disciplines across historical periods.

Both the rhyme and Hilliard and Norgate’s older sense of color phenomena speaks to the translational or transactional properties of color effects, effects that today we manage via that strange, grown-up, ring-bound, folded-out-and-up book The Munsell Book of Color, which allows us all to keep our colors straight, even in their absence.[34] The Munsell Code assigns each color a number, and as Bruno Latour writes of the soil color guide version used in fieldwork by pedologists, “the number is a reference that is quickly understandable and reproducible by all the colorists in the world on condition that they . . . use the same code.”[35] The book works by way of a “stupefying technical trick—the little holes that have been pierced above the shades of color” that enable you to align this or that colored something you have before you with its like and convert said something into its number referent. The book serves as an object lesson in a model of “circulating reference” that at every point in the translation of an effect or entity must attend painstakingly to what it means to keep that effect stable in a new medium.[36] Once upon a time, this desire for color fixity, to render effects permanent, required the limner to embark on a quasi-mimetic sympathizing with her palette. Now, such embodied knowledge migrates to the tactile certainty granted by a book that translates looking into touching, a book that comes allied to the industrial practices and the adumbration of resources necessary to relaying colors on a global scale. The Munsell Code registers thereby the replacement of the moral philosophically coded labor and techniques of the limner who worked with substances by another order of techniques. But the very existence of the code as the bibliographical form of an elaborated infrastructure attests also to the still necessary if differently deployed labor and resources necessary to keep phenomena “still.” Hospitality, become pure technique, reigns, but bypasses the substances whose labor and liking Teerlinc, Hilliard, and Norgate once had to cultivate.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Let’s return now to a moment just after the arrival of oranges and of orange in England, to a world reordered by the mobility of the fruit that hosts the color and gives it a name. Let’s arrive at the moment of Bonner’s liking.

Allure, circa 1600

Oranges began to arrive in England from Spain and Portugal at the beginning of the fifteenth century. They generally arrived in March or April, staying good until December. They arrived in quantity (tens of thousands at a time). They were not outrageously expensive, but neither were they cheap.[37] They remained an exotic, coded by the soil—Spanish or Portuguese—that grew them and by their status as a “corruptible,” one of those many entities, like us, subject to change. Come the seventeenth century, they would be sold in and around theaters as snacks or, on occasion, projectiles; on the street; as well as in bulk for eating, as holiday gifts, and as table decorations for the Inns of Court and well-to-do houses.[38] Seasonally, waves of “orange” and oranges entered the country, oranges coming to punctuate market stalls, dinner tables, finding their way into the hands and mouths of Londoners. And as with any imported commodity, the key to the fruit’s naturalization stemmed from the import of the concomitant skill and knowledge of its use (values).[39]

Oranges were not at first primarily an edible, finding themselves pressed to use as medicinal items, a fashion statement, a cleanser, as well as the more rarified kinds of uses I approached in my last chapter. Nor would they be so until the arrival of China oranges in the seventeenth century, which supplemented the waves of Seville fruits that typified the earlier periods. Moreover, their status as a southern fruit of Spanish or Portuguese origin meant that there was debate over whether northern English souls could properly digest them.[40] In an era when geohumoral theories modeled “Englishness” and “Spanishness” as tuned to different ecologies, eating an orange was to invite a potentially all too animate, foreign actor into your body—an actor that could well produce an indigestible “drift” or “flux” if you were not careful. Eat too many, take too little care in preparing them, and you might even find yourself embarked on an involuntary “becoming Spanish.”

Attempts were made to cultivate oranges in England, but they were not entirely successful. Shipments of orange trees tended to arrive in the spring and summer months. Upon arrival, they were transplanted to English gardens, grown usually in tubs, and moved indoors to sheds, greenhouses, or “orangeries” for the winter.[41] It proved difficult to grow trees that would flower and fruit, so the migration of orange trees north was accompanied by a bibliography of advice manuals serially translated into French, Dutch, German, and then English.[42] There even exists a translation and abridgment of Ferrarius’s Hesperides, which, as it heads north, shrinks from its two-volume, illustrated folio splendor to a slim quarto, first in Dutch and then in English, titled S. Comelyn’s The Belgick, or Netherlandish Hesperides (1683). The book reduces Ferrarius’s elaborate treatment of citrus lore to a minimum, focusing instead on the dos and don’ts of where to buy your trees, how to ship them, and under what circumstances you might be able to overcome their “unfruitfulness.” Torn between a Protestant dis-ease with Ferrarius’s Catholicism and a sovereign desire to transplant the trees, to render them “Dutch,” just as the book and then the tree, so it is hoped, were “Englished,” Comelyn justifies the omissions by claiming that “unnecessary Narration is Nothing but useless Labour.” Lose the art; lose the easy, idle otium of an orange grove; and maximize the labor you devote to “profit.” Ferrarius’s Herculean fetish likewise finds itself reduced to a general psychology or symptom, “whereunto every one must shew himself as an Hercules, and bend all his strength that he may break through by the waking Dragon into the most inward Garden, to satisfy the sweetness of his Invited Desires to this exercise.”[43] With no oranges of their own, the entire cultivation of citrus in Holland and England, if not yet Norway, comes coded as theft. But, ingenuity aside, such satisfaction that these northern Herculeses obtained from oranges still came from imported fruits.[44]

There were notable exceptions. But these required an inordinate commitment of time, resources, labor, and money, leading oranges and lemons to become one of the most technologized of fruits. Writing in the 1590s, Sir Hugh Platt describes a process practiced by a “Surrey knight” (Sir Francis Carew) that “extendeth generalie to all fruite not much unlike spreading a tent ouer a cherrie tree about four-teene dayes or three weeke before the cherries were ripe.” Platt recounts further that using this method, last Whitsuntide, he was able to present Sir John Allet, lord mayor of London, with “a score of fresh orenges.”[45] In 1601, John Tradescant, Lord Salisbury’s gardener, bills his employer for “8 pots of orangg trees of on years growthe grafted at 10 s[hillings]. the peece” collected while on a visit to Paris.[46] And in 1604, James I welcomes the Constable of Spain with a feast whose table was graced with “a melon and half a dozen . . . oranges on a very green branch” grown in England. A careful reading of that story indicates that Their Majesties split the melon with the constable but may not have eaten the modest number of English oranges, deploying them instead as a diplomatic superlative that signified the transplanting or grafting of Spain’s sovereign goods to England’s soil in the form of a sweet smelling diplomatic centerpiece.[47]

By and large, then, the translation (importation and cultivation) of oranges and orange trees to England unfolded as a series of failed, botched, or contested instances of Georgic. In England, this Virgilian mode exerted a shaping influence on the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, constituting a loose set of discourses or an “informing spirit” that moralized agricultural labor in the service of a growing sense of the importance of industry.[48] The immense popularity of Thomas Tusser’s home-grown Georgic Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry, published first in 1557, going through three editions in 1573 alone, and then “eleven more before the turn of the century,” testifies to the significance of the mode.[49] Arising from encomia for agricultural practices, in England, the discourse evolved into an “indistinctly loose” celebration of labor as some fungible mass or energy that might be applied to almost anything. Oranges arrived just at the moment in the sixteenth century when writers sought to downplay the socioeconomic particularity of the plow and the plowman as chief icons of the mode so as to make the discourse available for other kinds of ideological work in the making of persons, careers (political and poetic), nations, religious life, and profit. And these oranges posed a challenge, fueling, on one hand, a desire to develop technologies that might “English” them and, on the other, a sense of wasted, “useless,” or unthrifty labor—the oranges a delusive, seductive, foreign “corruptible” traded at the expense of staple commodities. Oranges came tainted with the same conflicting mix of signals that made the otium I explored in my last chapter so appealing.

Apprehended systemically, as an object of exchange, the fruit and the trees became subject to economic criticism given the reciprocal flow of capital out of the country on which their re/appearance depended. The price of all that orange and all those oranges required a commensurate absence of gold and silver that went abroad. When, for example, in the 1620s Gerard de Malynes updates sections of Thomas Smith’s A Discourse of the Commonweal of This Realm of England (1549) for inclusion in his Lex Mercatoria (1622), he bemoans the fact that some men “do wonder at the simplicite of the Brazilians, West India, and other nations . . . in giving the good commodities of their countries . . . for Beades, Bels, Knives, Looking-Glasses. . . when we our selves commit the same, in giving our staple wares for tobacco, oranges, and other corruptible smoaking things.”[50] Fetishists all, he seems to say; irrationality abounds. But Krugman and Obstfeld would be proud, for Malynes goes on to praise the mayor of Carmarthen, who organized a boycott of rotten oranges passed off as fresh by Spanish merchants in his town, driving down the price of this local “fetish.” Unhappy as he may have been that the Spaniards would only trade their wares for ready money instead of Welsh goods, still he knew the value of “gains of trade,” for the “Spaniard” in question “afterwards sold his Oranges better cheape, and bought commodities for his returne.”[51] The rationalizing rewards of exchange value stabilized by consumer action won out. But, in truth, this story is older still. Malynes’s oranges are relative newcomers. In Smith’s original, the “evil” or false corruptible in question was an apple and the offending merchant an Englishman.[52]

Criticism came also within the registers of good husbandry. The sheer amount of labor required to maintain orange trees in northern climes led Royal Society member, experimental scientist, arboriculturist, and radical cleric Ralph Austen to take the tree to task in A Dialogue or Familiar Discourse and Conference betweene the Husbandman and the Fruit-Trees (1676). Austen deinscribes the divine signatures in the trees of his orchard and provides transcripts of what the different trees say. These scripts put into words what Austen’s empirical observation of growing habits told him of their “fitness” to England’s soil. Austen’s husbandman remarks that there “are a sort of Trees that do not thrive, nor prosper, as other Trees do; what’s the reason? Seeing yee are as well planted, and preserved, as other Trees which grow neere unto you.” To which the fruit trees reply, “We are forreners; this is not our Native Country we were brought from beyond the Seas, from a warm Clymate; where we had a strong heate, and influence of the Sun; but we are here in a cold country, and it agrees not with us, we shall never grow, nor prosper, nor bring forth Fruits to please thee, or for Profit.” “I believe what ye say to be true,” replies the husbandman, going on to remark that “many Gentlemen of great estates, to please their minds, have sent for, and brought many rare Plants, and Trees, from forraine parts, out of the South Countries, of France, Spaine, Italie, and other Southerne Clymates and planted them in England, several degrees Northward; which though it will beare many kinds of good fruits to perfection, and ripenesse . . . yet it will not beare good Orringes, Lemons, Pomegranates, and such like Fruits of the South Countries.”[53] Better to grow English apples, whose “profitability” has been established by the experiments of the Royal Society.

But oranges still captivated. And because they could not be effectively “Englished,” they remained sovereign unto themselves, Spanish, perhaps, but twinned with a serial, handy, sweetness, and beauty all their own. Every orange constituted an event; interrupted the flow of stories and sense; warped them with its affecting presence—with a surplus of liveliness.

In the Paston Letters (1422–1509), for example, we learn that “Elizabeth Calthorp longs for oranges, though she is not with child.”[54] The letter passes over this longing, remarks it as an excess worthy of comment but offers no explanation. Cardinal Wolsey was famous for his predilection for taxidermied oranges or pomanders, “whereof the meat or substance within was taken out and filled up again with the part of a sponge wherein was vinegar and other confections against the pestilent airs; to the which he most commonly smelt unto, passing among the press [crowd or throng] or else when he was pestered with many suitors.”[55] In Much Ado about Nothing (1598), the falsely jealous Claudio names the guiltless Hero “a rotten orange,” claiming that

She’s but the sign and semblance of her honor

Behold how like a maid she blushes here!

O, what authority and show of truth

Can cunning sin cover itself withal!

Comes not that blood as modest evidence

To witness simple virtue? Would you not swear,

All you that see her, that she were a maid,

By these exterior shows? But she is none.

She knows the heat of a luxurious bed,

Her blush is guiltiness, not modesty.[56]

Here he throws this “rotten orange” back, metaphorically smacking the innocent Hero in the face, causing her skin to mimic the color of the fruit, to blush. And in his poem, “Employment 2,” George Herbert wishes that he “were an Orenge-tree, / That busie plant! / Then should I ever laden be, / And never want / Some fruit for him that dressed me,” inducting the peculiarity of the orange tree’s ability to flower and fruit at the same time into his attempts to craft prosthetic prayer machines.[57]

In each of these instances, as with Leonilla, a person and an orange exchange properties: both are remade in the process, taking on the properties of the other. Herbert wishes to become the orange tree, its fruit and flowers. He wishes to take within himself the tree’s ability to flower and fruit simultaneously, continuously, as he becomes a living florilegium of spiritual posies; or better, his poem shall comprehend the orange entirely, siphon off its vegetal being, pray on after he dies, the poem become his spiritual survivor. His poem would eat Francis Ponge’s “L’orange” but retain the “pip,” grafting its poetic and religious resonance to the root stock of orange. For Dame Calthrop, desire itself becomes “pregnant” with oranges; it may not be explained by the cravings that come from being with child. Instead, desire itself becomes that child. Dame Calthorp is pregnant with oranges. Wolsey’s pomander works a bit differently; indexes his orange fondness to concerns regarding his shepherding; raises doubts about his fitness as a shepherd who cannot stand the smell of his flock. But in each case, these exchanges set in motion a more or less readable material–semiotic transfer by which particles of orange-being impress themselves on our discourses and the forms of life they encounter turn orangey.

Much Ado’s Hero offers a particularly complex example. As an uncharacteristically clipped note in one edition of the play offers, Hero is pronounced rotten “perhaps because an orange may look sound but be bad inside.”[58] Here the orange functions as a little clock. The temporality of its ripening, its living or dying on, as it falls from the tree, occurs independently of what fate holds for its pith, which may remain intact and beautiful. In human hands, then, the orange becomes that most anti-Platonic of fruits, for its insides bear no relation whatsoever to its appearance. And in Much Ado, this “corruptible,” physiological peculiarity finds itself indexed to the instability of the female blush as a signifier (all at once) of innocence, shame, and guilt. Though, in this instance, the material–semiosis proves denser still, for in the theater, this “rotten orange” comes twinned visually with the “orange-women” who sell oranges to the play’s audience, and who, on occasion, also sold themselves. The rottenness of Much Ado’s orange goes mobile across this hybrid, gendered, animal–plant flesh as it is parceled out in differently animated forms. The passing of oranges from hand to hand, hand to mouth, and their contiguity with a similar set of economic and sexual exchanges produces a nexus by which oranges, human bodies, and gold exchange properties. Coincidentally, in Early Modern English, lemon and leman (lover) were homonyms, automatically inducting citrus into the amatory registers of the period by an accident of linguistic materiality.[59] So it is that the “civil” (Seville), Spanish, orangey, Claudio picks up a metaphorically rotten orange to throw at the “rotten” Hero and we watch a scene choreographed, perhaps, on the model of a pillory, in which the culprit is pelted with rotten fruit.[60]

It is important to recognize that these discursive forms of orange, this orangey archive, registers those moments when the temporality and chronology that are “orange” intersect with the differently mediated worlds of letter writing, life writing, theater, lyric, and still other political, sexual, economic, and spiritual chronologies. The lesson they offer lies in the nature of the associative process by which they come to signify. In each case, that of the hybrid orange longing Dame Calthrop; the puffed up, hollowed out, sweet-smelling wolf-in-shepherd’s-clothing Wolsey; the rotten-gendered- mishandled- orange- Hero; and the plantlike Herbert, we witness a different “performance” of the orange, a different declension or declination of the multiplicity that is orange as it gives itself to be grasped, as it fascinates historically particular pairs of hands and eyes and so produces different worlds. If there is a common script or pattern to these exchanges, it inheres to the way in which each of these orangey figures remarks a misfiring or misuse, an excess or surplus, that manifests in moral philosophical, economic, sexual, or political registers. The orange, as it were, interferes in these discourses, traumatizes or captivates them by and through its promise of expenditure and threat of theft or fault.

In A Lover’s Discourse, Roland Barthes names this topos “fâcheux/ irksome” and calls it “orange,” keys it to orange, or the historically particular, fictive orange Werther gives Charlotte in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774). He quotes the young man and adds his own gloss, extending his lines in paraphrase: “The oranges I had set aside, the only ones as yet to be found, produced an excellent effect, though at each slice which she offered, for politeness’s sake to an indiscrete neighbor, I felt my heart pierced through.” “The world is full of indiscrete neighbors,” Barthes offers, ventriloquizing Werther, “with whom I must share the other. The world (the worldly) is just that: an obligation to share. The world (the worldly) is my rival.”[61] Morphologically complex, the segmented orange gives itself to a plurality of consumers. It is made, so it seems, to be shared, even as each orange presses itself into your hand, offers itself as an “event” for you. The fruit gives itself to us but by that giving embeds us in a story of theft, from the world, from each other, as we derive our liking from out of this obligation to give, an obligation that the orange seems both to give and to offer to take away. Orange-being produces this paradox for us. It convokes multiple, incompatible, competing polities of animate or animal actors.

Of what consists an orange’s allure? What is the source of our taste or captivation? In one section of De Sapientia Veterum (On the Wisdom of the Ancients; 1609), titled “Atalanta for Profit,” Sir Francis Bacon offers one theory that explicitly writes the orange or golden apple into his early attempt to name and describe the form of the commodity. He does so by retelling Ovid’s retelling of the story of Atalanta’s race with Hippomenes in book X of Metamorphoses. As you remember, Atalanta’s amazing speed poses a bit of a problem for her would-be suitors. So Hippomenes relies on a gift of golden apples from Venus, which he throws in Atalanta’s path, distracting her, leading her to lose the race. Bacon offers this commentary:

The Fable seems allegorically to demonstrate a notable conflict between Art and Nature; for Art signified by Atalanta in its work (if it be not a little hindered) is far more swift than Nature, more speedy in pace, and sooner attains the end it aims at, which is manifest in almost every effect: you see that fruit grows slowly from the kernel, swiftly from the graft; you see clay harden slowly into stones, fast into baked bricks: so also in morals, oblivion and comfort of grief comes by nature in length of time; but philosophy (which may be regarded as the art of living) does it without waiting so long, but forestalls and anticipates the day. And yet this Prerogative and singular agility of Art is hindered by certain Golden Apples to the infinite prejudice of human Proceedings: For there is not any one Art or Science which constantly perseveres in a true and lawful course till it comes to the proposed End or Mark; but ever anon makes stops after good beginnings, leaves the Race and turns aside to Profit and Commodity, like Atalanta. . . . And therefore is it no wonder that Art hath not the power to conquer Nature, and, by Pact or Law of the Contest, to kill and destroy her; but on the contrary it falls out, that Art becomes subject to Nature, and yields the obedience of a Wife to her Husband.[62]

As Helen Deutsch comments, “Bacon’s golden apples make Atalanta a victim of the marketplace, seduced by the allure of ‘profit and commodity.’”[63] Art (technics) proves infinitely superior and speedier than Nature. But driven by a desire to derive an interest from the time it invests, it stops short, gets distracted. Nature moves at a different rate entirely. Its plants and creatures simply grow, just keep on growing; it figures a constant. Art (technics) eventuates itself, proves prone to “stopping” or halting, a bringing up short from the “proposed End or Mark.” It abandons the race and “turns aside” to ends other than those its designs posit. Nature just keeps on going. It does not recognize that there is a race and therefore wins.

Bacon genders this structure. Atalanta, we are told early on, responds to the apple “with the eagerness of a woman.” And so, on his reading of the myth, “Nature” plays the husband, “Art” the wife. But they make an odd sort of couple. For such sovereignty that “Nature” has over technics (and so us) plays as a little theft—our or Atalanta’s “obedience” is yielded through an involuntary if eager captivation that steals our ends from us, installing in us, instead, a desire for other ends still, for “golden apples,” sweet gold we can eat now. And the existence of “certain Golden Apples,” as Bacon’s generalizing syntax makes plain, transforms Atalanta’s historically particular apples into exemplary forms, cell forms, it’s tempting to say, of the “fetishism of the commodity,” by which Art is brought up short. For Bacon, then, the commodity form itself mimics or derives from the goldenness of these apples, from the fruits of a plant’s labors. The golden apple or orange, the self-rolling, gilded reproductive technology of the plant, already mimes and embeds the distractions of “profit and commodity,” which play here not as “the gains of trade” but as a delusive, enlivening, surplus or stunt and stunted telos that prevents “Art,” the “human” as technical animal, from attaining sovereignty.

Of course, Bacon’s little domestic allegory or discursive couples therapy holds only for as long we agree to suspend the presence of Venus, who, in Ovid’s version, and in Arthur Golding’s translation from 1567, narrates the scene. In these versions, the allure of the golden apples proves more complicated still, less or differently generalizable. In Golding’s version, Atalanta’s remarking of the first apple is described as “covetous”—a psychologized and religiously loaded term for desire—but the fruit is “rolling,” in movement, and it is that movement which seems to distract:

Then Neptunes imp her swiftnesse to disbarre,

Trolld downe at one side of the way an Apple of the three.

Amazde therat, and covetous of the goodly Apple, shee

Did step asyde and snatched up the rolling frute of gold.

With that Hippomenes coted her. The folke that did behold,

Made noyse with clapping of theyr hands.[64]

Atalanta steps aside, picks the apple up, examines it. We do not know what she does with the fruit. These moments serve as minimal instances of occupatio (dilation and delay) during which Atalanta becomes a spectacle for us and ceases to be a spectacle for the crowd, who cheer instead for Hippomenes. Her stillness, captivated by the movement of the apple, which she arrests, subtends or runs athwart the movement of the race that ultimately drives the story forward. The narrative moves on apace, but we, and Atalanta, do not. The golden apples introduce holes into the narrative, moments of repose or lapse. The action fits; the crowd’s attention shifts. And Atalanta’s fascination, much like Bonner’s liking, remains unreadable.

Roused from the pleasures of the fruit by the “noyse” of the spectators, Atalanta “recompenses” her “slothe” and catches back up to where she ought to be given her superior speed. She makes up for lost time. But the second apple “stays” her again. And, despite her “footmanship,” the legs of sense are held once again or suspended. No more details are forthcoming, however. Golding offers the second apple merely as a repetition of the first. As with Bacon, their serial deployment, along with Golding’s successive shortening of their name, renders them a generic placeholder for distraction, physiological, psychological, or otherwise. But the narrative also preserves this distraction, allows Atalanta a narrative space aside from the plotting of the race, which she exits and to which she returns after each rolling golden apple comes to rest, its mobility, its peripheral movement, manifesting as if an event. Golding captures, as it were, the rhythm of the commodity and of consumption. Its serial, punctuating calibration of the race registers the qualitative transformation that its finite quantity or titration allows. Atalanta stands fascinated. She is curious. But each curiously mobile apple sustains her attention for only so long. And so there comes another . . . and another.

The third apple tells a different story. Crestfallen that whatever he does Atalanta catches up, Hippomenes prays to Venus for help, and so she intervenes in what he seems to consider a mid course correction to her faulty “gift.” Hippomenes gives the third apple his best throw, “askew,” but when Atalanta seems to “dowt in taking of it up,” Venus assumes the first person, and tells Adonis that she put a “heavy weyght” to that apple, giving it such “massinesse” that Atalanta could not lift it. For Golding and Ovid, it seems as if Atalanta could refuse this last “golden apple” and interrupt the repetition compulsion. The golden apple’s allure might fail even as it continues to move and distract. But before that can take place, Venus alters the physics of the world so as to arrive at the desired outcome. And this intervention renders Atalanta’s refusal entirely virtual, a possible outcome, a thinkable but entirely preterit potentiality. For Ovid, then, the third apple appears less golden. Repetition pales. Atalanta learns. She seems less distracted, or has learned by distraction, seems on the point of recognizing the allure of the apple for what it is—“ something that,” as Jacques Derrida writes, “comes without coming,” that mimes a presence or a density that exists only by and through its mimesis, its movement, the hybrid mineral–plant form gold would take if you could eat it, if it were a plant.[65] And this insight, this curiosity as opposed to captivation, becomes the occasion for Venus’s course-correcting intrusion.

Venus black boxes the mechanism of distraction or allure such that we may read only the inputs and outputs. Oranges are sweet. Golden apples are shiny. They distract. Yes, perhaps we could refuse them. But no, they address themselves to us, and so, all of a sudden, we feel the weight or mass of their allure. Cognition comes too late to this particular game. Perhaps this is why Bacon feels he can delete the goddess entirely. She manifests as a personification of the governing physis of the world. For Bacon, then, the “massinesse” Venus attaches discloses merely the deeper inevitability of what, on his reading, meshes perception with a psychological drive for the false ends of localized and individualized profit. Bacon no longer has need of the goddess, for he derives a psychology stitched to an understanding of the form of the commodity from this scene of our captivation by golden apples, gold you can eat. We never find out exactly what passes between Atalanta and her three golden apples. Ovid and Golding grant us no access to her moments of fascination even as Bacon seems to take Venus’s word for it—so much so that he deletes her. Allure, then, cohabits with this absence in the narrative; its efficacy absents the recipient from what can be narrated. When Atalanta picks up a golden apple, arrests its movement, and considers it, the two constitute a time-bound stay, a hyperoccasional, almost event. Whatever unfolds between an orange and the animal with whom it is taken remains localized, historically particular, present only by and through its loss.

Is this structure what it means to eat? Is this the temporality of consumption, liking become a surplus of liveliness? Is this mode of distraction, following Pietz, what we must somehow find a way to steal?

“‘Oranges and Lemons’ . . . ,” circa 1665

“Say the bells of St. Clements.” Maybe you learned the rhyme as a child or read it in a novel. Maybe you did not. Here is how it goes:

You owe me five farthings,

Say the bells of St. Martin’s.

When will you pay me?

Say the bells of Old Bailey.

When I grow rich,

Say the bells of Shoreditch.

When will that be?

Say the bells of Stepney.

gold you can eat (on theft) [209]

I’m sure I don’t know.

Says the great bell at Bow.

Then it all gets a bit frightening: “Here comes a candle to light you to bed. / Here comes a chopper to chop off your head. / Chop, chop, chip, chop!”[66] The rhyme choreographs a street game in which two children “determine in secret which of them shall be an ‘orange’ and which a ‘lemon’; they then form an arch by joining hands, and sing the song while the others in a line troop underneath.”[67] When the rhyme approaches its gruesome finale, marked by the rising tempo, the two children repeat “chip chop, chip chop,” and “on the last chop they bring their arms down around whichever child is at that moment passing under the arch. The captured player is asked privately whether he [or she] will be an ‘orange’ or a ‘lemon’” and then joins the team of the said “orange” or “lemon.” Typically, the game ends in a tug-of- war between the two arbitrarily composed teams, leading to a victory for either oranges or lemons.

The text of the rhyme can be traced no further back than the eighteenth century. It appears, in a slightly different form, in Tom Thumb’s Pretty Song Book (1744), though there was a square for eight dance called “oringes and lemons” recorded in the third edition of Playford’s Dancing Master (1665)—but the text of this dance, if there was one, is not preserved.[68] According to Peg, a character in Edward Ravenscroft’s play The London Cuckolds (1682), which takes a postfire 1666 London as its scene, “oranges and lemons” is but “one of a great many things [they cry] in London.”[69] This is as far as the written record permits us to travel back into the origins of the rhyme, but it attests to the fact that by 1665, “orange” was a word you might expect to hear as you walked down the street in London. Generically, the rhyme belongs to that group of verses that recall what bells say, and such rhymes were marketed to parents as “artificial memory” devices for children in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[70] The text of the rhyme itself is subject to vigorous debate among local historians and antiquarians today, who lay claim to phrases from it for different churches that they wish to make more of a landmark. (The rival locations are St. Clement Danes in the Strand and St. Clements in Eastcheap, both of which boast Sir Christopher Wren–designed postfire interiors.)

“Oranges and Lemons” serves as a fitting emblem or jingle for the procedures by which, in the examples I have offered thus far, person and orange exchange properties, by which mobile, time-bound multispecies polities such as Atalanta and her golden apples come into being. The rhyme choreographs a scene of use and naming, the mutual nomination of person and fruit that serves as the privileged scene of encounter. But the rhyme exists now as a mute record of such encounters, a multiply authored, multitemporal archaeology, accreting references to differently timed peals of bells, landmarks, and half-remembered, half-forgotten “events.” It is pure anecdote—the archive become anecdote, catching particles of lost speech and practice, lost scenes of use. And yet, it connects, remembers the connection, even if, as with Atalanta’s moments of distraction, it enables no further inquiry. Did you know the rhyme already? Have you sung it? Shall you? It inducts its singers and listeners as “vicars of lost causations,” avatars of relations now gone which nevertheless it recalls.[71]

The rhyme invites its own order of reciprocal fetish work—all the archival labor needed not to recover but instead to posit the supposed labors, lives, and deaths lived by previous generations of Londoners whom it somehow touches. The endeavor may prove beguiling, inviting us to hallucinate a past, to catch traces of otherwise undocumented lives as we imagine this or that boy or girl, on the very edge of vision, unloading oranges from a barge on the Thames wharf or singing the song and playing the game. Such are the diversions enabled by the catachresis of bells saying things, bells that momentarily possess those who sing, those with ears to hear and tongues with which to vocalize the peal. The rhyme renders us mute as we are sung by phrases past whose meaning we can never know. The cries of London come (and go) again. “Chip. Chop.” But even as an immersion in ephemera, “a sadness without an object,” beckons, the rhyme puts us on notice also to the way these instances of exchange refer to encounters whose historical particularity cannot quite be rendered. For, as with a certain warder’s liking or taste for oranges, to render them is to rewrite their thing-like specificity, to steal them so that they may matter for us.[72]

Heard this way, “Oranges and Lemons” embeds a sense that our infrastructures come riddled with the remnants of these mobile polities, partial, time-bound practices or thefts that momentarily occupy a street for a game of “oranges” and “lemons” or their equivalent. And these polities unfold on and through and by way of an orange or a lemon, by and through their recruitment by the reproductive technology of a plant that interrupts human narratives, technologies of self, ways of being, nesting its own zoopolitical modality within the biopolitical articulation of our lives. The rhyme reveals also the tropic or rhetorical work of language games in managing these “events,” in establishing and maintaining routines, in keeping the built world built, even as its buildings disappear. And while the rhyme may invite a certain order of archive fever, it has within it everything we need to recognize that, in ecological terms, language arts, metaphor, rhetoric, remain key relays within a political struggle for citizenship, and for imagining alternate futures, by and through the way we contest what an orange, a lemon, or a refrigerator is, was, and those who join with them shall be. “Oranges and lemons” is a machine, in small, for writing different worlds. If you manage to lay claim to it or part of it today, mundane as it may seem, you may be able to direct tourist traffic to your landmark, sell a few more postcards and tea things, mend your church’s roof.

Of course, some might seek to police these spaces of encounter—to model particular moves and denounce others—precisely because they may prove productive, might err, might provoke possibility. In her short story “The Orange Man” (1801), Maria Edgeworth tells a story that she hopes might help young minds navigate the perilous London streets and avoid giving themselves over to a life of petty theft. In the story, we meet two boys: Charles, who “never touched what was not his own: this is being an honest boy”; and Ned, who “often took what was not his own: this is being a thief.”[73] Charles manages to resist the allure of the oranges in the orange-man’s basket, fights off Ned, gets a black eye; but for his pains, he has his hat “filled . . . with fine China oranges,” gives them away to his peers, wins their admiration (46–49). These same oranges fascinate poor Ned. “The sight of the oranges tempted” him “to touch them; the touch tempted him to smell them; and the smell tempted him to taste them” (38). That’s how desire works. Captivated by these oranges, Ned turns thief, ends badly. He receives no praise. “People must be honest, before they can be generous,” reads the moral (49). And perhaps it is so. But the story ends by asking “little boys . . . [to] consider which would you rather have been, the honest boy, or the thief ” (50). It makes thievery a choice; it encrypts the comparative disadvantages that, for some of us, render it a necessity of survival.

Obviously, I wish that the story had been interrupted by the “oranges and lemons” of St. Clements’s bells and that Ned might have had the chance to become an orange or a lemon, stolen a London street for the time the game took. The rhyme resists narrative, refuses its emplotment, orchestrates its own little time-bound theft by seeding the world with half-realized images that we have to fill in. It reminds us that world is littered with little thefts, nongeneralizable occupations, even if it too ends badly: “Chop, chop, chip, chop!” Moreover, under certain circumstances, the mere fact of singing “Oranges and Lemons,” badly, of giving your voice over to bells you have never and may not now hear, might matter, might actually do something.

Clocks Not Bells, 1949

“It was a bright, cold day in April and the clocks were striking thirteen.”[74] Against these clocks whose striking announces the altered routines and disavowed past of George Orwell’s 1984, Winston Smith is taken momentarily by a rhyme he hears and which he begins to hum, trying his best to lend his voice to bells he cannot remember hearing, perhaps has never heard. He’s alive to the way the Party implants false histories, and so he trolls around, acting on a note to self in his diary that “if there is hope . . . it lies with the proles” (85). He slums, eavesdrops on the cries of London, tries to talk to people and fails. He finds himself seized with “helplessness” when he questions an old man about the past—“ the old man’s memory was nothing but a rubbish-heap of details” (95). Still, Winston comes to sift the rubbish for this or that stray object that he finds “beautiful.” The words “beautiful” and “rubbish” circulate through the novel until they eventually connect and Winston owns the fact that he is on a quest for what he names “beautiful rubbish” (104). He is embarked on becoming an antiquarian, becoming a collector—trawling the remains of London for stray objects whose forms, whose fragmentary archives, somehow activate something in him that he does not quite know how to name. We join him as he considers renting a room from the old man we later learn is named Mr. Charrington, a room, Winston gasps, with “no telescreen” (100).

Mr. Charrington asks if Winston is interested in old prints and beckons him to join him in front of an old picture. Winston

came across to examine the picture. It was a steel engraving of an oval building with rectangular windows and a small tower in front. There was a railing running around the building, and at the rear end there was what appeared to be a statue. Winston gazed at it for some moments. It seemed strangely familiar, though he did not remember the statue. (101)

“I know the building,” says Winston. “It’s in the middle of the street outside the Palace of Justice.” “That’s right. Outside the Law courts,” adds the old man. “It was a Church at one time. St. Clement Danes. Its name was.” “He smiled apologetically, as though conscious of saying something slightly ridiculous, he added, “‘Oranges and Lemons’ say the Bells of St. Clements.” “What’s that?” asks Winston—who doesn’t know the rhyme. “Oh, ‘“Oranges and Lemons” say the Bells of St. Clements.’ That was a rhyme we had when I was a little boy . . . it was kind of a dance” (102). Mr. Charrington sings it over but he cannot remember the last line.