Join the colloquy

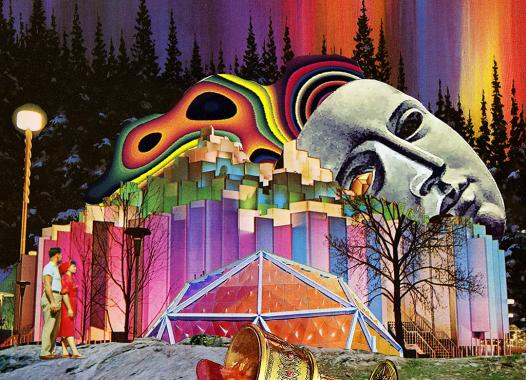

Comparing Literatures: Arabic, Hebrew, Persian, Turkish, Urdu

more

One answer is that we would simply know more. We would have more information, more data, to answer the questions with which the discipline is concerned. Some of those questions are older: What is literature and what does it do? and some are newer: What happens after/beside humans? A representative selection of questions can be found in the 2014-15 Report on the State of the Discipline from the American Comparative Literature Association. Doubtless, information from outside the Anglo-European sphere is improving this conversation.

Is it enough to know more and ask the same questions? What happens if there are different questions? It is hardly a surprising observation that literatures outside Europe have different constitutions and concerns. Trying to render them in a vocabulary intelligible to European or Anglophone audiences is a translation problem, and it becomes sharper when the ideas being translated are themselves self-conscious theories, attempts to carve reality at different joints from those at which Comparative Literature is accustomed to cut.

These observations push us to realize that the direction of travel is critical: do we build theories in European languages and then test them on the world, or vice versa, or neither?

This goal of this Colloquy is to ask and start to answer these questions: what should it mean for Comparative Literature to engage outside Europe? Where is the field now, and what could change? What does Comparative Literature look like when thought through the literatures of Persian, Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew, or Urdu?

The languages of this Colloquy broadly reflect the interests of the participants, many of whom come from a constellation of literatures with roots in a part of the world given various names: the Middle East, the Near East, the Islamic world, the Islamicate world, West Asia, and so on ad nauseam. The nausea comes from the inevitable problems of power and agency: the East was only Near or Middle for European colonialism, and academic neologisms such as Islamicate or West Asia scarcely have the power to hold sway within the ivory tower, let alone outside where the words people use have their own genealogies. Our aim in this Colloquy is not to readjust all the names and labels but rather to start with the literatures we know, and ask questions of our disciplines (literature, anthropology, translation) in the hope that some answers may prove useful when we think of other literatures around the world.

The Colloquy includes conversations that took place in recent years, book chapters and articles, and current think pieces—in addition to original scholarship, translation, and performance. It is open to new submissions.