First Edition

216

This is an excerpt from Una Chaudhuri's “Queering the Green Man, Reframing the Garden: Marina Zurkow’s Mesocosm (Northumberland, UK) and the Theater of Species”

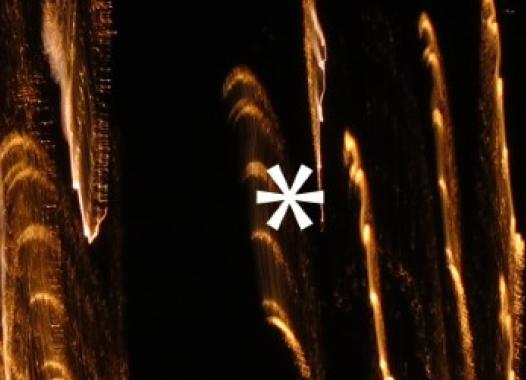

Marina Zurkow, Still from Mesocosm (Northumberland UK), autumn (2011).

Courtesy of the artist

Mesocosm is a video animation representing the passage of one year on the moors of Northumberland, UK.[9] One hour of world time elapses in each minute of screen time, so that a complete cycle lasts 146 hours: “Seasons unfold, days pass, moons rise and set, animals come and go,” around a centrally located and almost omnipresent human figure. The figures that appear suggest an open, even infinite, set of beings and phenomena, unconstrained by taxonomic limits: there are cows, owls, ravens, squirrels, foxes, men, women, children, humans in animal costumes, butterflies, refugees, caterpillars, swarms of insects, bats, rabbits, dumpsters, trucks, steamrollers, vans, calves, dogs, hares, fairies, dragonflies, inchworms, midges, spiders, hikers, bikes, horses, ponies, sheep, lambs, swallows, clouds, smokestacks, fog, pollen, shadows, garbage, leaves, petals, pollen, snow, rain, sleet, and wind. This is indeed, as the artist says in her notes on the work, “an expanded view of what constitutes ‘nature.’” It is also a capacious rendition of umwelt, staging the endless communicative events and interactions that shape the experience of human and other animals.

Martina Zurkow, still from Mesocosm (Northumberland UK), spring (2011)

Courtesy of the artist

No cycle is identical to the last, as the appearance and behavior of human and non-human characters, as well as changes in the weather, are determined by a code using a simple probability equation. This built-in indeterminacy is one of several features that align the work with queer ecology, which emphasizes the emergent, non-deterministic nature of evolution. In tandem with the work’s long duration (to see a whole year unfold takes almost a week), this indeterminacy implies and encourages a special kind of spectatorship: more casual and peripheral than concentrated, more peripatetic and mobile than fixed. It is a spectatorship that accommodates the rhythms of everyday life, and construes the work as a frame and context for those rhythms as much as a repository of images, events, narrative, and ideas. Experienced as a frame for the spectator’s ongoing lifeworld rather than as an alternate reality that is set against, intervenes in, or interrupts that lifeworld, Mesocosm functions like the landscape it depicts: a garden, that ancient and universal cultural framing of “nature” as a space for pleasurable visitation and temporary habitation.

Green man, Pembroke St. Cambridge, UK photo: Rex Harris

Photo by Simon Garbutt. CC BY-SA 3.0.

The special kind of enjoyment offered by gardens makes them particularly rich sites for ecologically oriented cultural theory, because the recreation they offer involves contemplating the re-creation of the natural world. The garden is the site of a complex—and potentially queer— circuitry that links human creativity to organic growth and, as such, a space and practice that challenges the ideologically influential nature/culture binary. One classic formulation of the debate around this binary (in its “nature vs. art” version) appears in The Winter’s Tale, where Shakespeare’s characters argue about whether horticultural practices like grafting are natural or otherwise. Perdita’s characterization of the cross-bred “gillyvors” in her garden as “nature’s bastards,” is challenged by her father Polixenes, who argues that:

Nature is made better by no mean

But nature makes that mean: so, over that art

Which you say adds to nature, is an art

That nature makes. You see, sweet maid, we marry

A gentler scion to the wildest stock,

And make conceive a bark of baser kind

By bud of nobler race: this is an art

Which does mend nature, change it rather, but

The art itself is nature.[10]

The interplay between art and nature that Polixenes asserts is nowhere better seen than in the garden, which also makes it a site for trying out, testing, or simply indulging— briefly and safely—new, non-normative identities. The central figure in Zurkow’s work is, I suggest, engaged in this experiment, and invites spectators to try out—or try on—an unaccustomed ecological role. Presence is a part of that role, but it is a strangely self-displacing, non-assertive presence, open to having the traditional boundaries of the individualistic self challenged and breached. This is a mobilized, aleatory, and queer presence, performing a new mode of species habitation.

One way to apprehend the key elements—as well as the creative potential and affective challenge—of this new role is to read it as a postmodern or queer version of the Green Man, another archetypal figure for the interdependence of art and nature. A common decorative motif of medieval sculpture, the foliate faces of this human-vegetable adorn the walls, doors, pillars, and windows of hundreds of churches, cathedrals, and secular buildings dating from the Middle Ages. Branches, leaves, and vines surround the faces of these figures, and often sprout from their mouths, noses, and ears. Figures of fertility and unbounded—not to mention boundary-breaching—growth, these species-crossing vegetable men were inherited from pre-Christian and pagan traditions of nature-worship. But they are equally at home in the contemporary, non-deterministic, and anti-essentialist biologies that inspire queer ecology, where boundaries are, as Morton writes, “blurr[ed] and confound[ed] at practically any level: between species, between the living and the nonliving, between organism and environment.”[11] The human figure at the (de-centred) centre of Mesocosm is a living, moving Green Man for our age, a queer response to the increasing threat of biopower in the Anthropocene. He is the protagonist of a new theatre of species.

Seeing Mesocosm as a theatre of species begins with noticing a seemingly simple structural feature of the work: the ever-changing scene depicted in the work is bordered on two sides by an expansive black area. This area functions as a frame, but one that can be entered, crossed, and occupied—though not, it seems, inhabited. When animals walk or run into the black space around the narrow band landscape in the middle of the screen—and also when the human figure himself lumbers or strolls into or out of it—that space transforms into something like the wings of a proscenium theatre, and momentarily turns the landscape into, as Zurkow writes in her description of the work, “a stage.”

Mesocosm’s landscape is haunted by the mode of theatrical representation that has dominated western theatre since Sebastiano Serlio introduced the principles of single-point perspective drawing into scene design in the 16th century. The theatrical aesthetic that developed soon after—illusionism—was greeted with great enthusiasm and launched a centuries-long love affair with realism that flourishes to this day.[12] I have argued elsewhere about the realist theatre’s complicity with anthropocentric and anti-ecological world views,[13] and recently Adam Sweeting and Thomas C. Crochunis have argued that the conventions of naturalist staging—especially its “rigidly dualistic conceptualization of space”—have shaped our experience of wilderness, and drastically limited the range of our imagination about nature and consequently our relationship to it.[14] This is exactly the limiting structure that Mesocosm addresses through a playful engagement with some of the most powerful and entrenched conventions of theatre.

This “gift” of illusionism was actually a costly exchange; with the illusion of depth now available to it, set design could supply astonishing effects of reality, but only—and always—within the confines of the picture frame, the proscenium arch. Pushed outside this frame, banished from the life-art dialectic that is the soul of theatrical process, the theatregoer went from being a participant to being a viewer. This new spatial order recast the spectator as a potential sovereign by suggesting an ideal position from which the perspectival effects are seen to perfection, known as the Duke’s seat. Not merely a spatial site, the Duke’s seat also modeled a new ideal of individuality, centrality, and authority for the ordinary theatregoer. But the bargain was a Faustian one: the average spectator’s chances of actually sitting in the “Duke’s Seat” were just as bleak as his or her chances of actually “mastering” the social world.

The psychology of perspectival spectatorship is as obfuscating as its ideology. In his 1996 book, The Experience of Landscape, Jay Appleton famously related various sub-genres of landscape painting to a set of biological needs and urges derived from animal habitat theory.[15] These genres, Appleton argued, are organized around certain strategic locations—prospect, refuge, and hazard—that are available to the predator or prey animal whose survival depends on successfully negotiating the various features of the land and its other inhabitants. Appleton singles out the picturesque genre as being especially pleasing because it places the viewer in a protected position, viewing the scene from a partially hidden and pleasantly shaded spot, the “refuge.” Any framing of a natural scene that confers such a position of safety on the onlooker is an instance of the picturesque, a guarantee that it is “only a picture,” and that the viewer is safely removed: “outside the frame, behind the binoculars, the camera, or the eyeball, in the dark refuge of the skull.”[16] Proscenium staging is a similar instance of constructing the “picturesque spectator,” the threatened or threatening human animal temporarily enjoying a moment of safety.

But as Gordon Rogoff puts it, theatre is not safe—or rather, its special power is squandered in producing illusions of distance, separation, and protected privilege.[17]

That spatial configuration supports both a theatre of isolated individualism as well as an anthropocentric theatre, framing the exemplary or heroic human figure and transforming everything non-human into mere scenery. Zurkow’s theatre-haunted landscape suggests ways to unseat the secure spectator and plunge him into the unpredictable terrain of life understood ecologically. The keys to this revisioning, or queering, of stage space are the position and behavior—and the astonishing art-historical lineage (from performance art, to painting, to video animation)—of the large human figure that dominates the foreground.

The main figure in Mesocosm is based on the Australian performance artist, designer, and drag queen Leigh Bowery, who helped to catalyze an extraordinarily interdisciplinary experimental art scene in London and New York in the 1980s. In Charles Atlas’s documentary film. The Legend of Leigh Bowery, a colleague of Bowery’s describes him as the “the greatest of the great outrageous Australians of the modern world,” a man utterly committed to challenging every assumption, breaching every boundary, and destroying every artistic or social convention he could lay his gigantic hands on.[18]

Charles Atlas, The Legend of Leigh Bowery, USA/France, 2002, 88 min

In his lifetime, Bowery’s “legend” was keyed to the extraordinary costumes he designed, built, and wore—vast, moulded carapaces of bright fabrics smothered in sequins and feathers. But, in a reversal that he himself would have relished, Bowery’s posthumous image is likely to be resolutely unclothed. This is thanks to the surprising role that Bowery played toward the end of his short life, as muse and model to one of the greatest of modern painters, Lucian Freud. Atlas’s documentary provides a delicious account of the moment this transformation occurred, this metamorphosis of a monstrously over-coded cultural icon into a mountain of flesh: Bowery had been invited to sit for Freud because his over-dressed style posed such a challenge to the renowned painter of disturbing, challenging nudes. But, while they were getting ready to start working, and while Freud’s back was turned, Bowery took off all his clothes having assumed Freud would be painting him naked.

The central figure of Mesocosm, then, is an incarnation of Bowery who has escaped the “too, too solid flesh” of Freud’s canvas to inhabit an eternity of jittery animation in a rural landscape. From his earlier life he has brought along another feature even more subversive here than it was in Freud’s painting: he turns his back on us. In a recent article entitled “The Seated Figure on Beckett’s Stage,” Enoch Brater shows how the absurdist master completes and deconstructs a historical process in which the seated figure on stage went from being an emblem of authority in the public sphere of Renaissance drama to a symbol of inwardness in the private worlds of 19th-century psychological realism.[19] The posterior view of the figure in Mesocosm initiates what I read as his challenging dialectic with anthropocentric stage presence, and thus as one strategy—though admittedly borrowed from painting— for the theatre of species he anchors. The strategy involves a kind of insistent embodiment: foregrounding biological presence, “backgrounding” psychological being.

Marina Zurkow, still from Mesocosm (Northumberland UK), summer (2011)

Courtesy of the artist.

Lucian Freud, Naked Man, Back View, 1991-1992. Oil on canvas, 183.5 x 137.5 cm. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY

However, the two things that most surprise us about Zurkow’s Bowery are also those that distinguish him from Freud’s: First, as already mentioned, he gets up and walks out of the frame. Second, he allows various small creatures not only to climb on him and sit on him but also to feed on him, producing the only specks of color—blood red—in the work. This scandalous symbiosis, based on a novel intimacy, suggests a queered updating of the ancient motif of the Green Man in the context of an anti-essentialist, relational ecology. The queer Green Man of Mesocosm contributes a personal and artistic history that is deeply relevant to his role in this “expanded apprehension of what constitutes nature,” a history that makes him the ideal protagonist for a post-anthropocentric, post-picturesque theatre of species. His travels between genders and genres have prepared him for the more challenging transit ahead, the journey between species.

The confidence with which Zurkow’s Bowery occupies this rural landscape represents the defeat of a long and contradictory cultural construction of the relationship between homosexuality and nature. As Andil Gosine writes in a recent article,

Homosexual sex has been represented in dominant renderings of ecology and environmentalism as incompatible and threatening to nature. [The construction of this prejudice is related to the fact that] In its early incarnations, North American environmentalism was conceived as a response to industrial urbanization. As homosexuality was associated with the degeneracy of the city, the creation of remote recreational wild space and the demarcation of ‘healthy’ green spaces inside cities was understood partly as a therapeutic antidote to the social ravages of effeminate homosexuality.[20]

Ironically, these very spaces began to be used by gay men looking for sex. When the gay practice of “cruising” forged an uncomfortable connection between homosexuality and public parks, it incited a new punitive discourse that sought to re-exclude homosexuals from nature, this time by equating their presence there with pollution, contamination, and danger to the community and its “family values.”[21]

Seated centre-stage yet unconcerned with the anthropocentric voyeurism, self-consciousness, and self-display of traditional stage presence, the Green Man of Mesocosm dwells in a theatre of species—all species—and nonchalantly performs a scandalous form of species companionship and ecological intimacy. The transgressive ethos and outrageous aesthetics of Leigh Bowery’s performance art and the extravagant physicality of Lucian Freud’s figures come together to queer the fragile landscape of the Anthropocene.

Notes

[9] Marina Zurow, Mesocosm (Northumberland, UK), 2011, https://www.vane.org.uk/exhibitions/mesocosm-northumberland-uk#:~:text=Mesocosm%20(Northumberland%2C%20UK)%20(,one%20year%20lasts%20146%20hours.

[10] William Shakespeare, The Winter's Tale, in The Norton Shakespeare, ed. Stephen Greenblatt (New York and London: W.W. Norton, 1997) Act 4, Scene 4, lines 89-97.

[11] Morton, “Guest Column: Queer Ecology,” 275-276.

[12] Notwithstanding the fact that Brechtian and other avant-gardes spent the last century exposing its complicity with essentially conservative (though ostensibly progressive) humanist ideologies and individualist psychologies.

[13] Una Chaudhuri, "Land/Scape/Theory,” in Land/Scape/Theater, eds. Elinor Fuchs and Una Chaudhuri (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2002).

[14] Adam Sweeting and Thomas C. Crochunis, “Performing the Wild: Rethinking Wilderness and Theatre Spaces,” in Beyond Nature Writing: Expanding the Boundaries of Ecocriticism, eds. Karla Armbruster and Kathleen R. Wallace (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001), 325-340.

[15] Jay Appleton, The Experience of Landscape (London, New York: Wiley Print, 1996).

[16] W.J.T. Mitchell, Landscape and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 16.

[17] Gordon Rogoff, Theatre is Not Safe: Theatre Criticism, 1962-1986 (Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 1987).

[18] Charles Atlas, Director, The Legend of Leigh Bowery, 2002.

[19] Enoch Brater, Ten Ways of Thinking About Samuel Beckett: The Falsetto of Reason (London: Methuen Drama, 2011).

[20] Andil Gosine, “Non-White Reproduction and Same-Sex Eroticism: Queer Acts Against Nature,” in Queer Ecologies Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, eds. Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 149-172

[21] Gosine cites the large number of reports of arrests of gay men in parks that explicitly mentioned the “trash” found at the sites of arrest—specifically condoms, condom wrappers, and tissues.

Join the colloquy

Join the colloquy

Queer Environmentalities

more

Scholars working to bring these two fields together argue that each has undermined its central goals by keeping aloof from the other: That ecological criticism has been fundamentally unable to broach the concerns of queer theory when it has privileged a version of "natural" that foregrounds heteronormativity; and that queer theory, for its part, has had no room for a consideration of the environment because the liberatory impulse of queerness has gotten much of its momentum from the turn away from nature, the de-coupling of human choices from a reigning "natural" order. But, queer environmentalists ask: Can an ecocritical enterprise—one aimed at revealing and reversing the destruction brought about by human-centric conceptions of environment—hope for a success if it fails to take into consideration the injustices of imagining the human as male and heterosexual?

This Colloquy takes its title from Robert Azzarello’s 2012 book Queer Environmentality, in which Azzarello argues that a synthesis of ecocriticism and queer theory can reveal that "the questions and politics of human sexuality are always entwined with the questions and politics of the other-than-human world." Criticism that attends to our queer environmentalities can enable profound resistances to, as Azzarello puts it, "conventional notions of the strange matrix between the human, the natural, and the sexual." Such approaches can reveal the Anthropocene as not only a period in which humankind has altered nature, but also as a period in which humankind has constructed the definitions of nature, and can throw into relief unarticulated valuations of scientific discourse and identity politics in making humans’ relationships with the non-human mean.

Since their budding in the 1990s in the pioneering work of ecofeminist critics such as Catriona Sandilands and Greta Gaard, queer-ecological methods have gained momentum across humanistic disciplines, periods, and national boundaries. This Colloquy highlights exciting new work in literary and cultural histories and presents dance and performance, film, music, urban studies, and political ecology. It showcases a range of approaches, from postcolonial to trans theory, to objects of study spanning our aesthetic productions and our political, economic, and rhetorical responses to the challenges of managing climate change and natural resources. The pieces featured here expand conceptions of environment and sexuality to include the human(-made) and the non-human, the intersections of bodies' outsides and insides, minds and discourses, making possible new ways to think filiation and affiliation, desire and sex, realisms and un-realisms, aesthetics and politics.